The South China Sea: tiny islands, high stakes

Timothe Jekel

The South China Sea is home to tiny islands, claimed by multiple countries. An international legal framework exists for this kind of issue: the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), or the Montego Bay convention, put into law in 1982. Most countries worldwide ratified it. The text provides guidelines for navigation, borders and natural resources dispute resolve. The “constitution of the oceans” says a country’s sovereignty extends 200 miles off its shores, an area called the exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

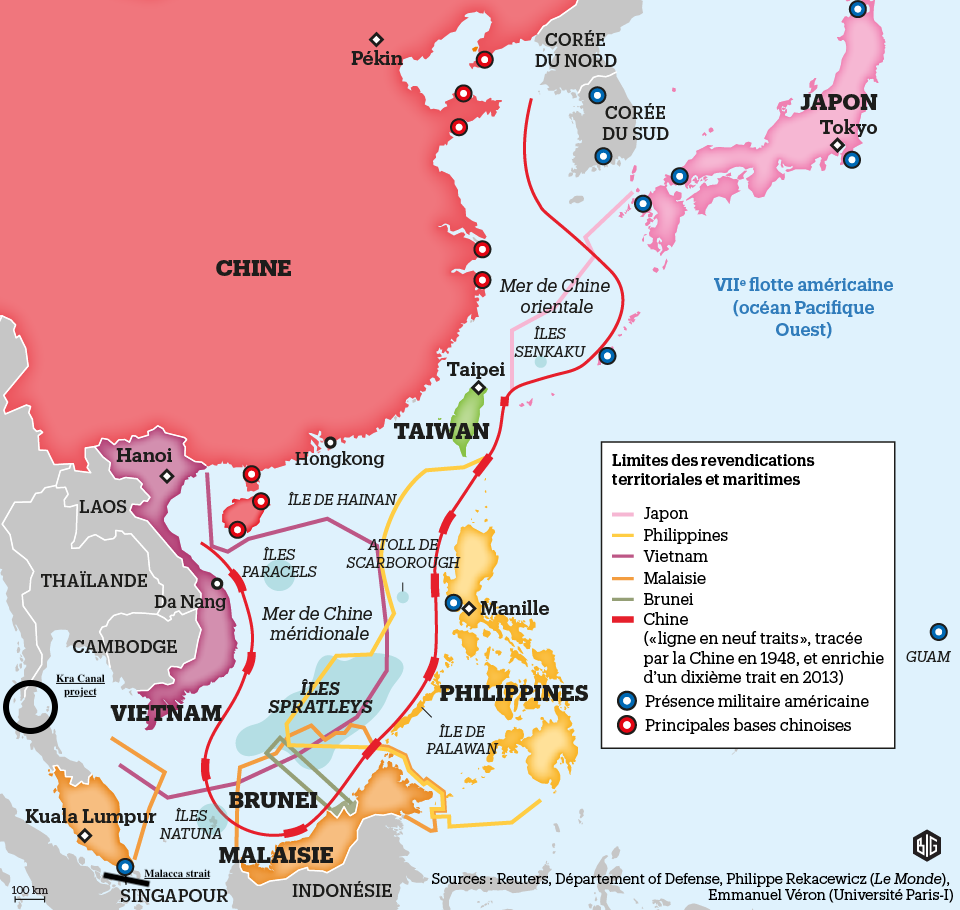

The South China Sea contested waters (Reuters, DoD, Le Monde)

Every country in the region, which includes the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei, bases its claim to the South China Sea on the UN framework, except China. Although China has ratified the UNCLOS in 1996, it ignores the EEZ 200 miles rule and refers to its historical rights to bring legitimacy. In red on the map, the controversial “nine dash line” within which China considers the waters sovereign territory.

To that extent, the South China Sea is an embodiment of Chinese global geopolitical ambitions. It claims these islands because they yearn to control the maritime route leading up from the EMEA (Europe, Middle East and Africa) region to their shores. Indeed, 30% of the world’s shipping trade flows right in those contested waters. Also, the islands draw attention because of the rare metals and offshore natural resources. It’s estimated to hold 11 billion barrels of oil, 109 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 10 percent of the world’s halieutic resources (Vox), something China cannot ignore as they seek to foster their domestic growth and self sufficiency.

Adverse claims are fueling feud between the Middle Kingdom and its southern neighbours. Manilla challenged Beijing’s claims in 2013 and won through the UNCLOS dispute solving mechanism. China turned a deaf ear on The Hague’s court ruling but feared a vietnamese complaint and negotiated directly in 2014. Anyway, the Chinese military holds an aggressive stance and has been running a policy of fait accompli. Based in Hainan island, the navy has been poldering islets and building military bases on some, in order to ensure their ownership and defense. This has been done gradually in order to avoid conflict.

Focus on the Spratly islands (Courrier international — Atlas de l’eau)

The Spratly and Paracels islands are driving South East Asian countries’ political agenda. Those are gathered in a supranational organization dubbed ASEAN. As Vietnam holds the chairmanship in 2020, the issue is to be addressed. Yet, hope for a swift and sharp conflict resolution is thin. In 2002, ASEAN and China agreed on a first Declaration of the Conduct of Parties (here). It lays out the way for peaceful conflict resolution. A new Declaration is set to be negotiated in 2021.

One thing is keeping China away from more imperialism: the 7th fleet. The Obama administration decided to initiate a “Pivot to Asia” and to increase their scrutiny of Chinese military ambitions in the region. The US has several military bases closeby (first map) and runs more and more “Freedom of navigation” operations. Drills have been conducted with three other nations, skeptical of Chinese looming dominance in the region: India (which sees the String of Pearls strategy as a threat to its national security), Japan and Australia (since 2020). Hence, the group’s Malabar naval exercises are set to deter any Chinese threat to regional security. US sanctions have also been announced against Chinese companies that contributed to the islets poldering. Plus, a Biden administration is likely to keep striving to deter China from its maritime ambitions.

Hence, the US is a stability force in the region. In order to offset Chinese dominance, ASEAN countries prop up a closer alliance with the US, including Vietnam, something hard to believe given History. The fact that China agreed to negotiate with Vietnam in 2014 is proof that it wants to avoid sparking a regional conflict that could escalate and turn into a global conflict with US alliances.